Tacos and timepieces with Mitch Greenblatt, and the most leftfield vintage watch collection you’ve ever seen

D.C. HannayThose who know me know I’m an avid enjoyer of oddball timepieces. As you might guess, my Insta feed is chock full of vintage horological thirst traps from the likes of @misterenthusiast, @teenage.grandpa, and @the_lost_spring_bar, but there’s one that towers above, at least in its sheer scope: the online museum of curiosities known as @horolovox. Mitch Greenblatt and I have been online acquaintances for a few years now, but it was just last fall that we had the chance to briefly say ‘sup in person at a watch event. Turns out that we both live in upstate New York, so plans were made to meet up for dinner in the near future.

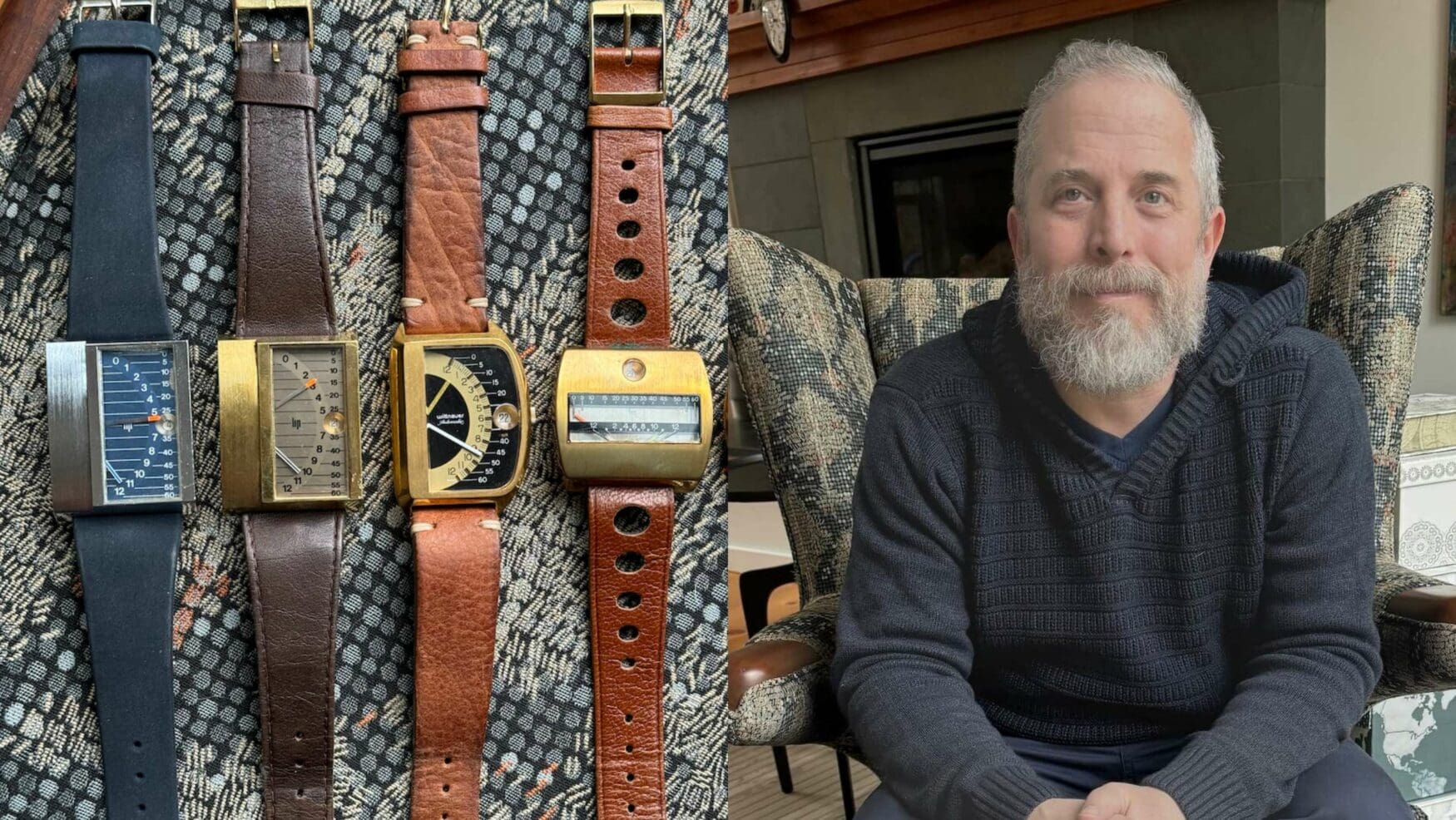

Schedules and the fates finally aligned, and Mitch and I recently hit one of my favourite Hudson Valley spots for a round of barbacoa tacos, tequila, and a mini vintage watch meet, which turned out to be anything but mini. I brought a modest watch roll of four vintage pieces, along with the Navitimer on my wrist, but Mitch was packing serious horological heat.

In addition to his renown as a watch blogger, buying and selling vintage pieces, and curating quite the substantial collection, Mitch also co-authored a fantastic book, Retro Watches: The Modern Collector’s Guide. It’s a lavishly photographed tome, chock full of obscure references and fascinating history. And here laid out on the bar were example after example of those impossibly rare timepieces from the book. I was breathless. Someone was definitely not kidding around. Seeing this before me, it became clear why the collection deserved its own book, and also explained why Mitch started his own microbrand in 2013, Xeric, undoubtedly inspired by his particular collecting bent. I needed answers.

D.C. Hannay: Mitch, tell me a little about your background. You were an illustrator before watches came along, correct?

Mitch Greenblatt: I had a few careers before watches came along. I’m an art school dropout who ended up in Los Angeles working in film and TV art departments. My claim to fame was working in the props department of Pee-wee’s Playhouse. Ultimately, production design wasn’t what I was looking for, but long story short, it led me to a career as an illustrator in Brooklyn.

DH: So, how does an obsession like yours begin? When were you bitten by the radioactive horological spider?

MG: The end of my illustration career was around the same time I discovered vintage watches, specifically alternative case shapes, space-age designs, and early digital technology ranging from 1960-1975, first at outdoor markets like Portobello Market in London and the New York City flea markets, but of course through eBay and dealers I knew from around the globe. This led me to Switzerland, to score everything from vintage 1972 Spaceman watches that had been in deep storage since then, to all sorts of unusual chronographs, mechanical digital jump hours, and vintage electronic watches, including the earliest examples of LED and LCD displays.

DH: Have you always been into, shall we say, left-field watch designs, or did you collect more traditional pieces early on?

MG: It was the Spaceman watches of the early 1970s that Andre LeMarquand created to commemorate man’s accomplishments in outer space, along with the moon landing, that first got me fired up about what other oddball mechanical watches might be out there from that era.

DH: Truthfully, how out of hand has it become? Are you a collector on the level of, say, Cheap Trick’s Rick Nielsen, whose vintage guitar collection has seen thousands come and go, and still numbers in the hundreds?

MG: Retro Watches is a book I was asked to help create, and it contains a large portion of my personal collection, which probably ebbs and flows around the 300 mark.

DH: It’s hard to wrap my mind around a number like that. Getting to those watches, you have an insane collection of retrograde models, including some really rare ones like several Lip Secteurs and the Wittnauer Futurama. What’s the attraction for you? It feels like a lot of your taste reveals an affection for automotive design, especially American cars of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

MG: Yeah, totally, it’s a speedometer style of telling time that does something for me. Those linear timelines that are super easy to read, that have a very cool flyback mechanism that launches the hour and minute hands back in an instant. It does something dramatic, unlike a traditional watch, it’s noticeably “alive”, as you can feel the jump on your wrist. Plus it has an extra mechanical module on top of those ETA movements that also adds so much interest to me.

DH: We grew up right around the same time, so I feel like we saw a lot of the same things. My tastes have always leaned toward what I call action-hero pieces, like divers, pilot’s watches, and racing chronographs. That’s probably down to the fact that I’m not exactly gentle with my wristwatches. A good chunk of your collection leans hard into bold, graphic dials, asymmetry, and the sort of futurism that recalls something you might find in the art department of a mid-century ad agency. Am I in the ballpark?

MG: You’re smack dab on home plate. It all begins with (automotive and industrial designer) Richard Arbib, who worked for Hamilton in the fifties. Richard Arbib was one of the first watch designers to create unique timepieces that weren’t just round or square, they were entirely invented and reinvented shapes. They could be automotive in reference, or even otherworldly, with strange, asymmetric shapes. He incorporated the look of everything around him, especially cars and spaceships. Elvis wore them, plus they were cutting-edge technology, way ahead of their time with electric-mechanical movements. Arbib bridged the space-age aesthetic to the sixties, and allowed future designers to think outside the circle.

DH: I’ve also noticed that you have a lot of early digital watches in the collection, from mechanical to electronic. Some of them really must have seemed like the future when they were released, like the Bulova Accuquartz or Zenith Futur Time Command, which both used LED displays. It’s funny how LEDs were pretty much erased from the watch market a few short years later. Would you call yourself a fan of anachronistic tech?

MG: Sure, I’m a fan of things that lasted for a very short time due to rapid developments in technology, but more specifically, I love how Swiss mechanical watch companies reacted to the newfangled digital watches from Japan. Out of fear, they created jumping hour watches to appear like a modern digital watch, literally printing the numbers to mechanically rotate into little windows as if they were being illuminated.

DH: Girard-Perregaux recently put out an updated reissue of their digital Casquette, which was rather well received. Do you consider it a vindication of your tastes when one of these designs comes back?

MG: It’s very cool to see brand after brand embrace their history, especially outdated ones like the Casquette. Plus, it makes my vintage versions more valuable! I think it’s a natural cycle. A modern or original design can often go under the radar in its own time. While a sense of nostalgia is obvious, the truth lies more in the appreciation of something ahead of its time. Consumers seem to always catch up with a good idea, especially when brands are more open to exploring some of their past hits – and misses – for a new generation that often relishes the nostalgia of their childhood.

DH: You’ve also got a very rare Hamilton, the Odyssee 2001. Tell me the story behind that one.

MG: It’s a watch born from the collaboration between Hamilton and Stanley Kubrick, the director of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Kubrick had commissioned Hamilton and other brands to reimagine their products in the future, and the watch and clock Hamilton produced were remarkable looking. Hamilton ultimately timed a more conventional commercial watch release to coincide with the movie’s opening. There were two styles, including one that was nearly impossible to find.

DH: I know you’re not really a Rolex guy, but another rare bird in your collection is a Midas Cellini designed by none other than Gérald Genta. How did that come about?

MG: Yeah, occasionally I find a vintage Rolex Cellini that looks much more like a vintage Patek from the seventies. The King Midas is a no-brainer and an essential watch of the era.

DH: So, what are you still on the hunt for? Where does a collection like this go from here?

MG: There are many I’d like to replace that I’ve sold in the past. Not sure why I dwell on those, but I’m sure that’s not uncommon. I have to admit to acquiring my grail watch, a pre-owned Urwerk from 2007, the Purple TIALN (Titanium Aluminum Nitride), with a rare angular crystal for the 103 series. One of only a handful made, this very rare colorway and crystal design gives me satisfaction like no other mechanical watch in my collection.

DH: That’s quite the exclamation point, and a great place to wrap up. Thanks, Mitch!